|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

|

LOW INCOME COMMUNITIES: Do low-income communities form a large part of the customer base and the majority of the unserved population? Will the bulk of future utility customers be low-income households? As a result of declining economic performance and urbanisation, many urban centers are expanding at a fast pace, and are increasingly characterised by rising poverty levels and a growing informal sector. As a result a disproportionate number of urban residents are housed in informal settlements that are not planned, often unserved and sometimes illegal. To meet future requirements, utilities will need to develop the skills and knowledge to adequately respond to demand of low-income households, who will comprise the majority of potential new customers. THE FACTS: • The Challenge of Urbanisation in Africa See: Regional Overview - Africa See: Serving the Urban Poor: An Overview of Regional Experience

|

||||

|

||||

|

• Poverty Line = $1 per day Income is not the only measure of poverty. The poor lack education. They suffer from malnutrition and poor health. They are vulnerable to natural disasters and to crime, and they lack political freedom and voice. But in a world where 1.2 billion people live in extreme poverty, obtaining less than $1 a day, increasing economic opportunities is fundamental. Over the past decade, the proportion of people in extreme poverty declined more in some regions than in others. In East Asia, especially in China, poverty rates have declined fast enough to meet the goal in 2015. Most other regions could achieve the goal, if economic growth continues and income distributions do not worsen. But Sub-Saharan Africa lags far behind, and in some countries poverty rates have worsened. Slow growth meant increased in both the share and number of the poor in the 1990s leaving Africa as the region with the largest share of people living below $1 a day. Urban poverty has grown faster than rural poverty, owing to massive migration from rural areas to the cities, with the incidence of urban poverty now matching that of rural poverty. From: http://www.developmentgoals.org/goals-poverty.html

WHAT SHOULD THE PRACTITIONER DO ABOUT IT? In 1999, the World Bank institutions and the IMF (International Monetary Fund) initiated an approach intended to strengthen domestic policies and use external assistance more effectively for poverty reduction. Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP) describe a country's macroeconomic, structural and social policies and programs over at least a three-year horizon, explicitly addressing strategies to promote broad-based growth and reduce poverty. They are prepared by low-income member countries through a participatory process involving domestic stakeholders as well as external development partners, including the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. For more information, see the IMF’s "Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers: A Factsheet" (August 2002). Indivdual PRSPs are also available on line and include documents from more than 20 African countries, including Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Cote d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia. See: Responding to Demand

|

||||

|

||||

|

NATIONAL POLICY ON SERVICES: Does national policy recognise the right of all people, including the urban poor, to access to a basic level of water and sanitation services? Are appropriate policies backed by supporting legislation and appropriate commitment? Urban and rural water supply policy and related legislation often do not address the specific problems of informal settlements. Although equity and poverty concerns are highlighted in policy, it has often been assumed that the particular needs of low-income consumers can be addressed in the same manner for all consumers. However the informal nature of these settlements necessitates a different approach that starts with recognition of the necessity of extending services to these settlements. Utilities have often been barred from serving these areas by policy, legislation or regulations that restrict access or hinder implementation (e.g. inappropriate standards). WHAT SHOULD THE PRACTITIONER DO ABOUT IT? Designing water and sanitation projects to meet demand is a key task. Demand is defined as an informed expression of desire for a particular service, measured by the contribution people are willing and able to make to receive this service.

|

||||

|

||||

|

From: Designing Water and Sanitation Projects to Meet Demand See also: Regional Workshop on financing Community Water Supply and Sanitation, White River, Mpumalanga, South Africa, November 26-December 2, 1999. Demand Response Approach (DRA). See also flyer: Ten Steps Toward Serving the Poor. Building Capacity to Deliver Services to Low Income Communities.

|

||||

|

||||

|

LOW INCOME AS CUSTOMERS: Does the utility have a policy and strategy that treats all households, whether in planned or unplanned and/or informal settlements as legitimate customers? Are low-income households in unplanned and/or informal settlements traditionally accepted as “legitimate customers” by utilities? Many utilities do not have a clear mandate from Government to serve low-income households that reside in informal settlements. As a result, many utilities have not focussed on developing an understanding of the needs of their low-income customers and do not have the capacity, products or programmes tailored towards improving services in these areas. The high priority placed on urbanisation and poverty eradication by many Governments, will make it necessary for utilities to take a more proactive approach towards serving the poor. THE FACTS: WHAT SHOULD THE PRACTITIONER DO ABOUT IT? • One service option does not fit all consumers – segment the market and respond to demand. |

||||

|

APPROPRIATE STANDARDS: Are the service and technical standards – often designed for formal/planned settlements - appropriate for informal settlements? Opening up standards for review and revision is essential to improving services to low income communities. Technical and service standards designed for formal and often middle and high-income areas, are often assumed to be adequate for addressing the needs of low-income communities. In many cases these standards are now inappropriate for the majority of urban dwellers who fall below the poverty line and do not reside in planned areas. Flexibility and innovation are required to enable service delivery in difficult physical environment.

|

||||

|

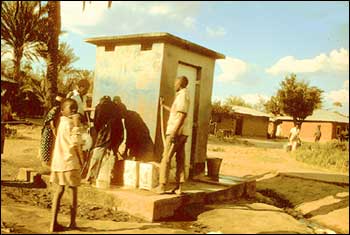

ALTERNATIVE SERVICE PROVIDERS: Does the utility recognize the proliferation of alternative service provider despite the extent of the services they offer? In the absence of utility services, small-scale providers, including private and non-governmental organisations have stepped in to fill the gap. In some countries, these providers account for up to 70% of service provision and offer a wide range of services that are tailored to their customers needs. They often go where utilities are unable to and recover costs where utilities have failed to do so. Some have noted that “Vendors are human pipes.” THE FACTS: Small-scale providers of infrastructure services are proving to be more responsive than utilities to needs of poor consumers. They might be delivering water services by tanker, transport services by minivan, or electricity through mini-grids or household solar panels. They make their services affordable to the poor by using cheaper technology or permitting flexible payment. Regulators are customarily hostile to these alternative providers. The interests of the poor would be better served if regulators treated them as valid service providers and brought them under a regulatory umbrella. See: Micro Infrastructure: Regulators Must Take Small Operators Seriously. See Reports: See: Intermediate and Independent Service Providers: Filling the Gaps

|

||||

|

LOW-INCOME ‘VOICE’: Do the low-income have a ‘voice:’ do they have the right to a vote but not to a service? Due to their status as “illegitimate customers” low income households are often unable to demand a service from utilities. This ‘lack of voice’ limits their choices. Due to the informal status of the settlements they reside in, they are sometimes poorly organised and lack access to formal institutions that can represent their views or speak on their behalf. Although they are often considered an important voting block, their political influence does not translate into policy decisions in their favor. Electoral promises are not fulfilled.

|

||||

|

UNPLANNED SETTLEMENTS: Is the unplanned nature of low-income settlements physically difficult to provide services and at a higher cost? The most common denominator in all informal settlements is poor geographical location. Physical constraints to infrastructure and service provision constitute the primary challenge to most utilities. The high cost of laying infrastructure in rocky, hilly and waterlogged areas is also a result of inflexible standards which can not be met without disruption to life and . This is especially the case because informal settlements are by nature unplanned. WHAT SHOULD THE PRACTITIONER DO ABOUT IT? Promote the upgrading of slums and regularization of squatter settlements, within the legal framework of each country. In particular, embrace the aim of the Cities without Slums initiatives to make a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers by 2020. Overview of upgrading in Africa What should upgrading programs include?

How should upgrading programs be financed?

Who should do what?

How to scale-up: unresolved issues, challenges and next steps.

See: "Experience with Urban Upgrading in Africa" (PowerPoint presentation) For detailed country assessments, see: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cote D'Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Namibia, Senegal, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia See: Declaration on Cities and Other Human Settlements in the New Millennium, in Istanbul+5. See: Taking Urban Upgrading to Scale: Where are the Bottlenecks?

|

||||

|

TARIFFS: Do the tariff structures disadvantage the poor, as well as the unconnected, second or third-hand customer? The majority of low-income households are not directly connected to utility networks. Many share a yard tap with several households located within the same compound. Others purchase water through vendors who deliver water door to door, or from kiosks and neighbours who sell water at a fixed location within proximity of their dwelling. As a result tariff structures that set ‘lifeline’ or ‘social blocks’ to serve the poor, often miss the mark. Many low-income households pay up to 10 times per litre consumed for water purchased second- or third-hand from intermediaries. THE FACTS: Direct subsidies are an increasingly popular means of making infrastructure services more affordable to the poor. Under the direct subsidy approach, governments pay part of the water bill of poor households that meet certain criteria. This approach was first used in water sector reforms in Chile in the early 1990s and is an alternative to the traditional method in which governments pay subsidies directly to utilities, often allowing the price of water to fall below economic costs indiscriminately. See: Designing Direct Subsidies for the Poor—A Water and Sanitation Case Study, Vivien Foster, Andres Gomez-Lobo, and Jonathan Halpern, May, 2000. The full article explains how simulation techniques can be used to inform the design of direct subsidy schemes, ensuring that they are both cost-effective and accurate in reaching the target population. WHAT SHOULD THE PRACTITIONER DO ABOUT IT? Tariffs, Subsidies and the Poor in the Urban Water Sector was the focus of the 12th Urban Think Tank held in Mumbai on 3-4 April 2001, and explored suggestions on policy actions. Three presentations were made: (i) Reflections on Water Pricing and Tariff Design by Dale Whittington; (ii) Types of tariff and subsidy models prevalent in Indian cities by Usha Raghupath; and (iii) International models of tariffs and subsidies and their distribution effects by Javier Jarquin. The issues that came out of sessions were summarized as:

For more details, Pushpa Pathak, Urban Specialist at wspsa@worldbank.org. Other lessons from Asia: five recent papers discuss the experience on tariffs and subsidies in the south Asia region, and may provide insights for Africa as well. (pdf downloads)

|

||||

|

REGULATORY STRUCTURES: Are the regulatory structures and capacity to administer weak? Are the regulations inappropriate and outdated? Many informal settlements function outside the legal and regulatory framework of the city. By nature their informal status often means that they do not meet planning standards, do not have full legal status, and do not comply with regulations. Weak or no enforcement is a direct outcome – one cannot enforce what does not legally exist – and leads authorities to turn a blind eye to activities that are considered a necessary evil. THE FACTS: Nontraditional infrastructure service-providers supply many low-income consumers in slums and urban peripheries in developing countries. Technological change has eased entry by new providers. But the current approach to private participation in infrastructure typically gives exclusivity to a local monopoly for a long period. In return, the monopoly utility is obligated to provide service to all in the area at a certain standard, charging a rising block tariff and using some cross-subsidies. This approach can inadvertently erect barriers to improving service for low-income households. Policymakers therefore need to rethink their approach to private participation transactions and their regulation. In particular, they need to focus on facilitating new entry. See: Reaching the Urban Poor with Private Infrastructure, Penelope Brook Cowen and Nicola Tynan, June 1999. WHAT SHOULD THE PRACTITIONER DO ABOUT IT? As long as alternative service providers remain 'illegal', they are difficult to monitor and regulate. Once recognized as playing a vital role in water service delivery, and when accommodated through a contractual relationship, it is possible to put in place rules to enable monitoring of quality, guidelines on pricing and to convert what was originally recorded as water losses to income. Illegal activities are often charged at a premium due to the high stakes/risks involved. Once risk is reduced through recognition and regularization, the small-scale private sector is willing to invest resources and to improve services to consumers. Monitoring by the utility (enforcement of contract), other members (peer pressure) and consumers (voting with their feet) provides some checks and balances, and all parties have some degree of protection under the law. See: Delivery of Water Supply to Low-Income Urban Communities through the Teshie Tanker Owners Association: A Case Study of Public-Private Initiatives in Ghana, Mukami Kariuki, Water and Sanitation Program and George Acolor, Ghana Water Company Limited, Accra-Tema Branch. See also: Water Sector Reforms in Zambia - NWASCO. This is an example of government action in addressing the failure to deliver acceptable levels of service. Critical analysis of the problems revealed that they were not necessarily technical, but more the result of weaknesses in the institutional, legislative, and organizational framework of the sector. Government refocused policy at promoting and encouraging development of the private sector so as to make it the main thrust of economic growth, and formulating various measures aimed at facilitating a conducive environment for private sector participation. See: Improving Access to Infrastructure Services by the Poor: Institutional and Policy Responses. Penelope Brook and Warrick Smith. Background paper for the Private Sector Development Strategy Paper, World Bank, Washington D.C., October 2001. (46 pages)

|

||||

|

INTEGRATION OF SERVICES: Are water, sewerage, sanitation and hygiene services adequately integrated? Many utilities are only responsible for water supply. A few have responsibility for sewerage, almost none are responsible for on-site sanitation, and only a handful support hygiene and environmental health education programmes. As a result, public health objectives are often not met and environmental health objectives are considered somebody else’s responsibility. WHAT SHOULD THE PRACTITIONER DO ABOUT IT? An example from Durban, South Africa shows a successful integrated approach. Despite being a modern industrial city and the largest port, many Durban communities are without basic water and sewerage services, and there is poor maintenance and management of these services. Historical imbalances resulted in communities placing little value on the proper use and maintenance of sewerage systems. Abuse and misuse of sewerage systems was costing the Council about R6 million per year. An education and public information programme was established to inform people that the provision of improved services must be accompanied by corresponding responsibilities. Components included an initial education campaign to schools and communities with focus on long-term sustainability. The following were incorporated: a curriculum guide, a roadshow, street theatre performances, establishment of an education awareness centre and the development of a legal framework for pollution management. See: Sewage Disposal Education Programme, Durban Metro Water Service, Department of Wastewater Management, Durban, South Africa.

|

||||

|

PRIVATE SECTOR PARTICIPATION: Is the private sector involved and what are the implications for the poor? Private sector participation (PSP) is increasingly viewed as a means by which efficiency and effectiveness of water and sanitation utilities can be improved. However, PSP is often considered as potentially negative for the poor. Much depends on how contracts and policies are structured, how targets for extending services are specified and financed, and on Government’s ability to regulate operations of private operators. In designing PSP the role of alternative service providers, who may play a major role in the sector should not be overlooked. Where possible they should be integrated into service provision arrangements. THE FACTS: Countries suffering from low incomes, limited administrative capacity, and an unfavorable government track record—some of the poorer countries of Central and Eastern Europe, for example, or Sub-Saharan African countries emerging from long periods of internal conflict—struggle to attract private investors to their water sectors. The settings they offer are not conducive to the large, long-term sunk costs characteristic of water sector investments. But there are a number of ways to reduce the costs of contracting and increase the attractiveness of deals. Strengths and weaknesses of options should be assessed, including building up from a management contract to a full concession in a two-step approach, simplifying contracts, contracting out some regulatory functions, and increasing the predictability of regulatory discretion. See: "Privatise Water Sypply in Nairobi", Editorial, The Nation News, June 21, 2000. "Insights Into Ghana's Privatisation Process", Mariam Ayoti. "Privatised Water Service in Ghana Boosts Efficiency", Mariam Ayoti. WHAT SHOULD THE PRACTITIONER DO ABOUT IT? When addressing policy issues surrounding private provision of infrastructure and the poor, it is first important to assess whether agreement exists on issues underlying ideas for shaping good policy among the professional community. Surveys often include the following issues: demand, priorities, public awareness, supply networks and technology, economies of scale, land tenure, exclusivity, micro-entrepreneurs, informal suppliers, quality, and subsidies. The private sector is starting to take on a growing responsibility for delivering water and sanitation services in low-income countries. However, the private sector can take many forms. Scattered examples of small-scale private sector operations, either independent or with community-based support, show that poor households not connected to a formal network often receive improved services from private sources. Technological innovations are providing ways for these small-scale providers to expand and improve the quality of their service, and at the same time raising a challenge to the standard assumption that economies of scale are pervasive. Poor households show a high willingness-to-pay for services. Future policy should look more carefully at the barriers - such as technology requirements and land tenure requirements, or billing schedules and connection fees - that prevent them from doing so. There is recent awareness that PPI does not automatically overcome the difficulties of extending network services has encouraged innovations in contract regulatory design to try to improve the incentives. Shifting the focus towards explicitly pro-poor contract and regulations may encourage policy-makers to consider formally opening the market to alternative private suppliers, and to facilitating co-operative relationships between formal utilities and informal operators. See: "Private Solutions and the Poor: Perceptions of Private Participation in Infrastructure and the Poor." Melissa Houskamp, World Bank. June 2000. See: "Private Participation in Infrastructure and the Poor: Water and Sanitation" Nicola Tynan, George Mason University. June 2000. See also: The Private Sector and Water Sanitation—How to Get Started, Penelope J. Brook Cowen. January 1997. See: Private Participation in Infrastructure in Developing Countries: Trends, Impacts, and Policy Lessons. Clive Harris. Private Sector Development. The World Bank. 2002. 60 pages.

See: Favourable Policy and Forgotten Contracts: Private Sector Participation in Water and Sanitation Services in Stutterheim, South Africa. Janelle Plummer. Working Paper 442 01. GHK International, London, November 2000. (62 pages)

See: Transitory Regime Water Supply in Conakry, Guinea. Claude Menard and George Clarke. Policy Research Working Paper 2362. World Bank, Washington, D.C., June 2000. 53 pages.

See: Toolkit: Selecting an Option for Private-Sector Participation in the Water & Sanitation Sector. Prepared by World Bank staff, academics, privatization advisers, government officials and water operators. Task Manager Penelope Brook. Funding support from the Department for International Development (U.K.). The World Bank 1997. 176 pages.

|

||||

|

||||