|

AgricultureThe main problems facing agriculture are a declining supply of water and a decrease in the quality of the water. As the population continues to increase so does demand for food, but the amount of water available to produce that food does not increase. There is competition over the water in the rivers. Water quality is also an issue, since runoff from fields makes rivers more saline, carrying off soluble mineral salts as well as excess nutrients from fertilizer such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. As a result the water may be too salty to use for irrigation further downstream, since most crops cannot cope with salty water. (Segelken, 1997). There are two main areas of agriculture where water is an issue: livestock and crops. Too much water is used for livestock production, making American meat consumption unsustainable. As far as crops are concerned, the current irrigation systems are often inefficient resulting in water loses and runoff. The government's policy of subsidizing crops is also a problem since it promotes growth of water intensive crops in some dry areas. Continue reading for more background on the problems facing agriculture or read our solutions to these problems. LivestockIn 2000, fresh water withdrawals for livestock throughout the entire US totaled 1,980,000 acre feet (USGS, 2000). This includes all water associated with on farm uses such as waste disposal, cooling, drinking water for the animals, and does not include the water used to irrigate the feed crops. When one takes into consideration the fact that fields of grain must be grown to feed the cattle, the amount of water used to produce meat increases dramatically. For grain-fed beef to get from farms to consumers requires 3 682 liters of water per kilogram of food produced (Beckett, 1993). Even crops that are often thought of as water-intensive, such as soybeans and rice, require only about 2,000 and 1,900 liters per kilogram, respectively. Other crops, such as wheat and potatoes, require even less water (Segelken, 1997). Livestock also contributes to severe degradation of the environment. Soil erosion on overgrazed pasture land, which represents about 54% of all American pastures, is estimated to be about 100 tons per hectare per year. In addition to decreasing soil quality and productivity, erosion causes soil to run into waterways, increasing turbidity and harming aquatic life (Segelken, 1997). Small particles in the water block sunlight from reaching bottom-dwelling plants, reducing photosynthesis, which results in decreased oxygen production and limited production of primary food sources. The silt in the water also irritates fish directly; sight-feeding fish have a difficult time capturing prey and silt can interfere with gill mechanisms, causing suffocation. (Clearing Ponds, 2001, p. 1) The increased amount of particulate matter in the water also makes it more expensive to treat for human use. In addition to directly harming the environment, raising livestock is costly in terms of energy consumption. On average, meat production requires about eight times more fossil fuel than plants. In fact, the grain being fed to American livestock could feed about 800 million people or generate about $80 billion/year if exported (Segelken, 1997). The following map indicates locations of major cattle farming operations. The majority of cattle farming occurs west of the Mississippi River, which is the area of concern for the Mission 2012 project.

Source: Cattle and calves - inventory: 2002. (2002). Retrieved 11/13, 2008, from http://www.nass.usda.gov/

The problems caused by livestock are exacerbated by the fact that Americans are eating more meat than ever before in the country's history. Specifics on increases in meat consumption can be seen in Table 1 by the USDA. Isolating only American beef consumption, the average American's beef intake requires 772,800 gallons of water annually. TABLE 1

Source: US Department of Agriculture. Agriculture Factbook 2001-2002: Profiling Food Consumption in America. (2002). Retrieved 11/13, 2008, from http://www.usda.gov/factbook/chapter2.htm

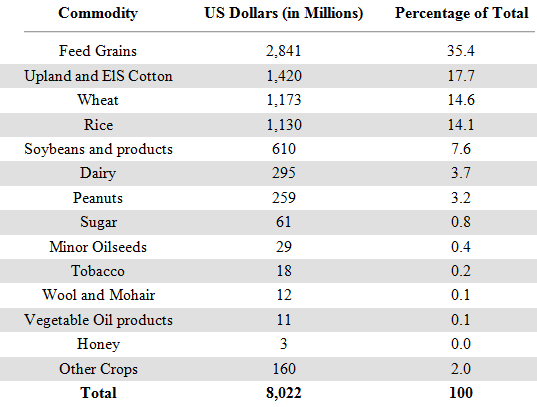

Crops and IrrigationCrops also use a lot of water. According to the United States Department of Agriculture in 2002, 16.6% of all harvested cropland in the United States is irrigated. Water withdrawals for irrigation in the Western states total 143,000,000 acre feet per year, out of the total 153,000,000 acre feet over the whole US. Groundwater in the west is being depleted by about 57,800,000 acre feet per year in 2000 as a result of agricultural dependence on this water source, while irrigation claimed 85,350,000 acre feet of surface water in the same year (USGS, 2000). Hutson (2004) estimates that in that year 40% of water withdrawals in the United States were used for irrigation. California has the highest rate of water withdrawal in the United States at 34,200 thousand acre feet per year (Hutson, 2004). The diagram below illustrates the surface, groundwater and total water withdrawals for irrigation by state in the year 2000. The first major part of the problem is inefficient irrigation. Out of the many different irrigation systems used, surface systems are both the most common and the least efficient methods of irrigation. In surge flow systems plants absorb 75% of the water and in conventional furrow systems it is as low as 60% (Amosson, 2002). 59% of the irrigation in the entire southwest region of the U.S. occurs in Wyoming, New Mexico, and California and it primarily uses surface systems (Hutson, 2004). There are more efficient systems, but they are not widely used throughout the southwest. For example in these three states only 24% of the irrigation systems use sprinklers. The sprinkler systems include the center-pivot systems of low-elevation spray application (LESA) which is 88% efficient, mid-elevation spray application (MESA) (78%), and low energy precision application (LEPA) (95%) (Amosson, 2002). Additionally, the increase in population over the next 100 years will put a tremendous strain on the current water supplies as well as the current food production capacity. We should remember that the problems affecting water supply in the American West are also a global issue. The United Nations estimates that a 14% increase of water allocation to irrigation practices is required to support the population of the world by 2030. The global population is currently growing at a rate of 80 million per year, but current water sources cannot maintain that amount of withdrawal for very long. As an alternative solution, Seckler et al. concluded in a 1998 survey that increasing the effectiveness of irrigation could meet over half of the water demand increase in 2025 (Howell, 2001, 281-289). TABLE 2

Image Source: USDA Budget Summary and Annual Performance Plan. (2006). Retrieved November 23,2008 from USDA Web site: http://www.usda.gov/

The second part of the problem for agricultural water use is that the types of crops grown are not always suitable to the climate and environment. Government subsidies exacerbate this problem since they encourage growth of water consuming crops in areas where such farming is not economical and is inefficient. In 2000 field crops (corn, wheat, rice, cotton, alfalfa, pasture) accounted for 58.6% of the total irrigated acreage (USDA, 2002), but in general the gross production value of field crops, at $524/acre, is less than that of other crops such as fruits and nuts ($3,314/acre) and vegetables ($5,171/acre). Some field crops are then only economically viable because they are subsidized. For instance, in the 2000 US Farm Bill, farmers were paid an extra 52cents for every bushel of wheat sold and were guaranteed a price of $3.86 for the period 2002-2003 and $3.92 for 2004-2007. The Bill allowed total crop subsidies of $619 billion, of which $53 billion consisted of direct payments in support of field crops. But field crops tend to be more water intensive since the type of plant requires more water and they also have a greater tendency to be surface irrigated. Therefore subsidies promote water intensive farming (Cooley, 2008). Table 2 gives details of subsidies provided in 2006. Lower water prices for farmers encourage wasteful usage. A specific example is the federally built Central Valley Project in California. This is a mass of infrastructure which supplies water for irrigation at prices between $7.14 and $56.73 per acre-foot. Since these prices are so low, by September 2005 agricultural users had only repaid 18% of the initial investment. Thus they are receiving the water at an unrealistic price which does not promote conservativeness as much as it could (Cooley, 2008). |

|