Lab 4

Lab 3 review

Last lab, we learned how to bootstrap confidence intervals. Reminder of how we did that:

library(tidyverse)

library(languageR)

# resample with replacement, take the mean

resample_mean <- function(values) {

samples <- sample(values, replace = TRUE)

return(mean(samples))

}

# repeat resampling num_samples times to get distribution of means

resample_means <- function(values, num_samples) {

replicate(num_samples, resample_mean(values))

}

# use empirical quantiles of the distribution of means to get 95% CI

ci_lower <- function(values) quantile(values, 0.025)

ci_upper <- function(values) quantile(values, 0.975)

# for each class, compute mean and bootstrap CI

weight_summary <- weightRatings %>%

group_by(Class) %>%

summarise(mean_rating = mean(Rating),

ci_lower_mean = ci_lower(resample_means(Rating, 1000)),

ci_upper_mean = ci_upper(resample_means(Rating, 1000)))

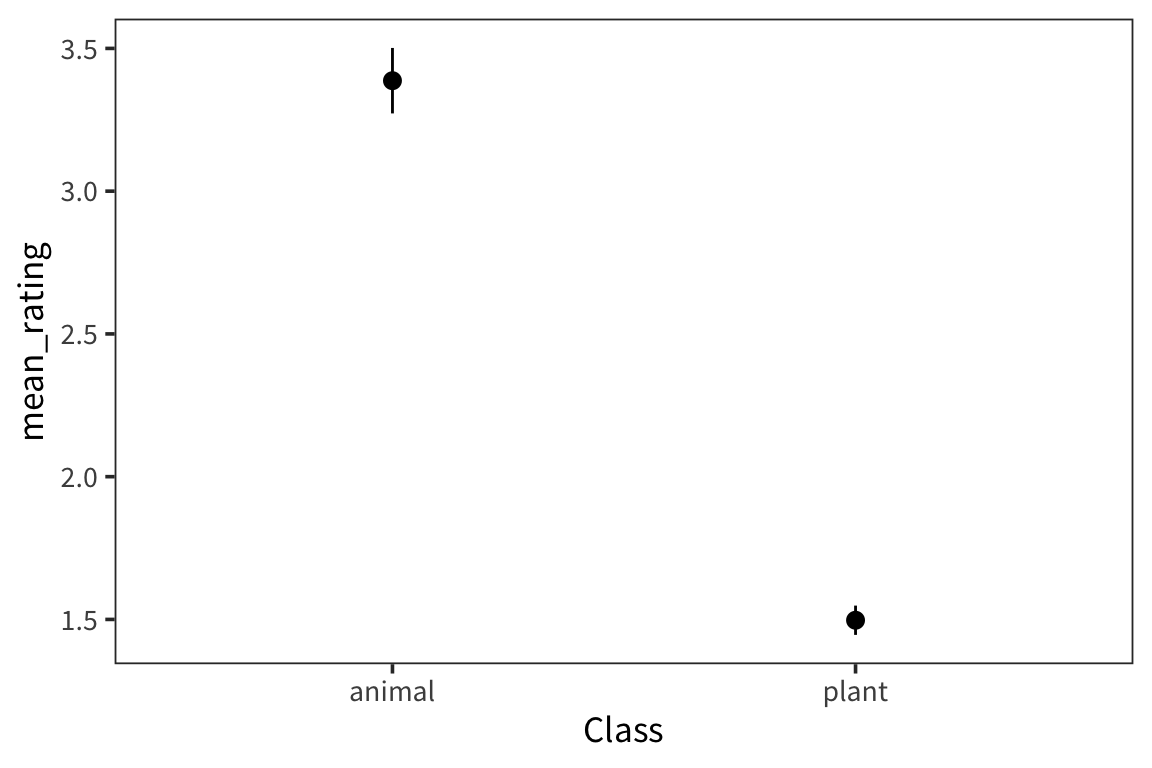

ggplot(weight_summary, aes(x = Class)) +

geom_pointrange(aes(y = mean_rating, ymin = ci_lower_mean,

ymax = ci_upper_mean))

Your new advisor has a super yolo attitude and tells you he’s okay with your confidence intervals containing the true value of the mean 70% of the time rather than the usual 95%. What would you need to do differently to make this change? Do you expect your new CIs to be narrower or wider? Why? Change the functions above to reflect this, compute new CIs, and compare your new and old CIs.

You decide means are too boring and want to look at another property of the data. Pick a different statistic of interest, compute its value for the data, and bootstrap a confidence interval of your estimate.

A sudden heatwave wipes out 80% of your data. Subset the dataset to the remaining portion and recompute CIs. Are the new CIs narrower or wider? Why?

Recall that earlier we computed CIs in a different way, from a parametric model – we used the fact that the sampling distribution of the mean of any distribution should be approximately normal given a large enough sample size (by the Central Limit Theorem). Compute CIs using that method and compare them to bootstrapped CIs.

In what situations might it be better to use parametric methods or better to use bootstrapping?

70% CIs:

ci_lower_70 <- function(values) quantile(values, 0.15)

ci_upper_70 <- function(values) quantile(values, 0.85)

weight_summary <- weightRatings %>%

group_by(Class) %>%

summarise(mean_rating = mean(Rating),

ci_lower_mean = ci_lower_70(resample_means(Rating, 1000)),

ci_upper_mean = ci_upper_70(resample_means(Rating, 1000)))

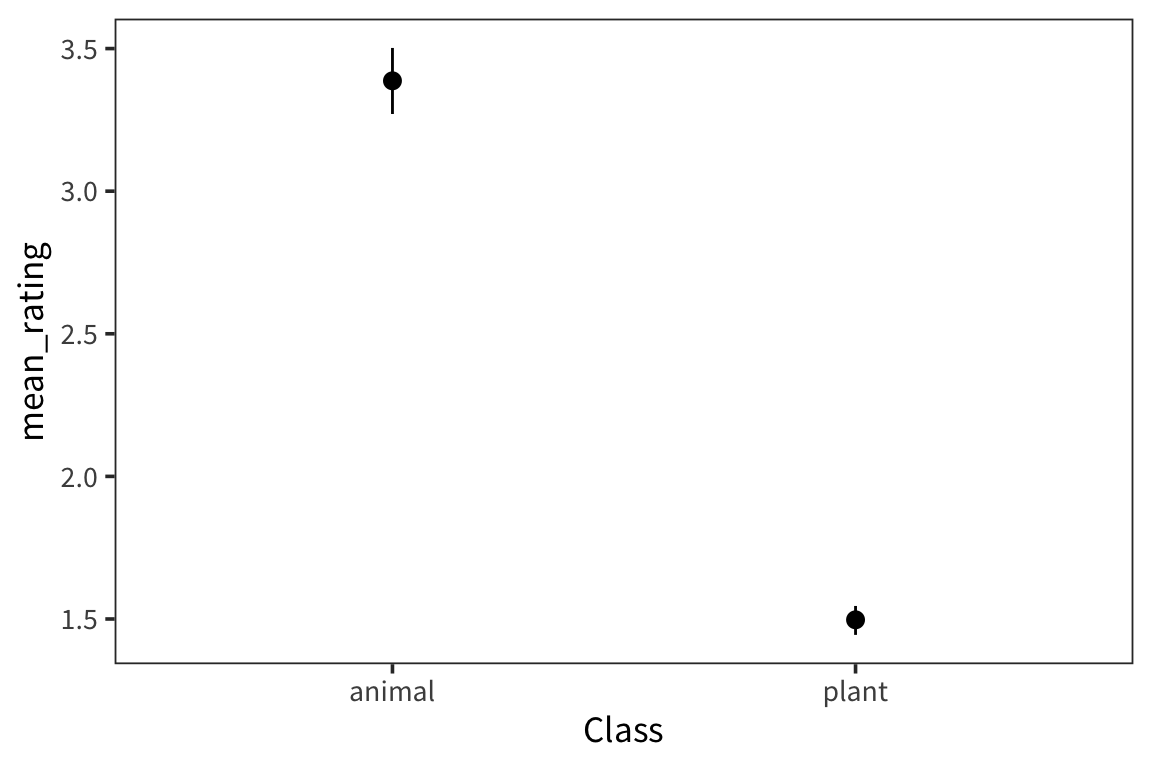

weight_summary## # A tibble: 2 x 4

## Class mean_rating ci_lower_mean ci_upper_mean

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 animal 3.39 3.32 3.45

## 2 plant 1.50 1.47 1.52ggplot(weight_summary, aes(x = Class)) +

geom_pointrange(aes(y = mean_rating, ymin = ci_lower_mean,

ymax = ci_upper_mean))

Standard deviation instead of mean as statistic:

resample_sd <- function(values) {

samples <- sample(values, replace = TRUE)

return(sd(samples))

}

resample_sds <- function(values, num_samples) {

replicate(num_samples, resample_sd(values))

}

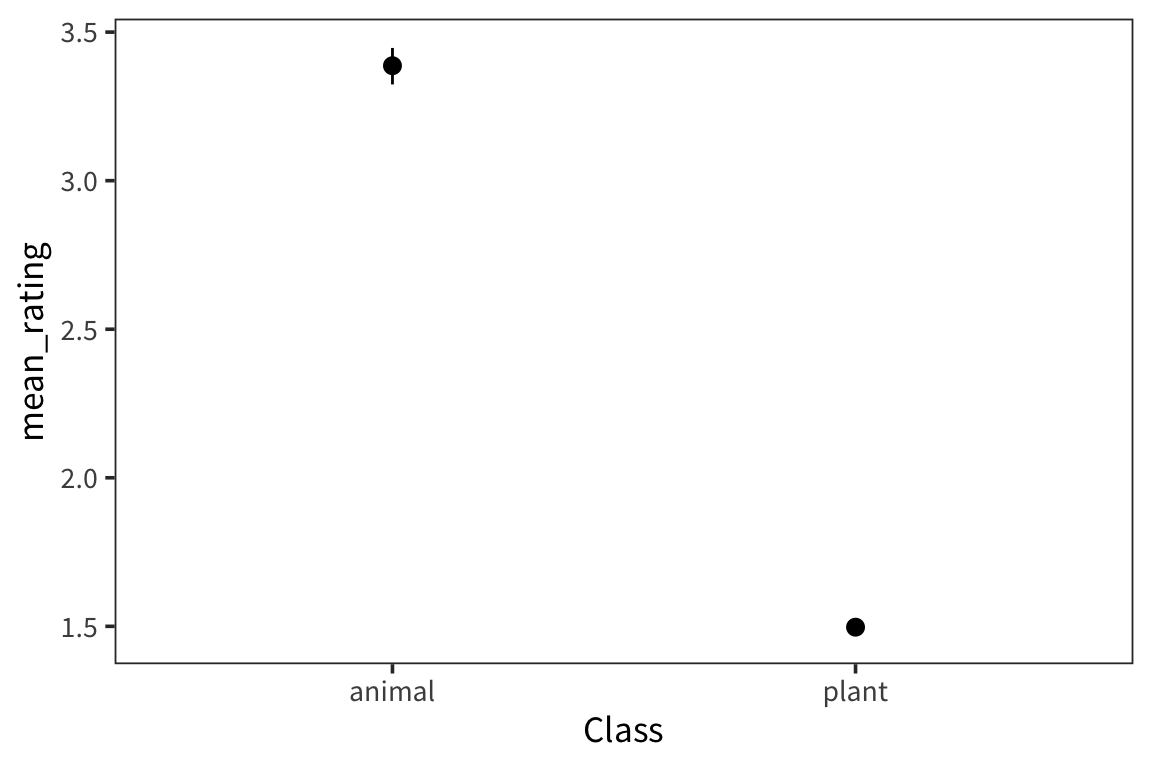

weight_summary <- weightRatings %>%

group_by(Class) %>%

summarise(sd_rating = sd(Rating),

ci_lower_sd = ci_lower(resample_sds(Rating, 1000)),

ci_upper_sd = ci_upper(resample_sds(Rating, 1000)))

weight_summary## # A tibble: 2 x 4

## Class sd_rating ci_lower_sd ci_upper_sd

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 animal 1.77 1.71 1.83

## 2 plant 0.692 0.642 0.738ggplot(weight_summary, aes(x = Class)) +

geom_pointrange(aes(y = sd_rating, ymin = ci_lower_sd, ymax = ci_upper_sd))

Less data:

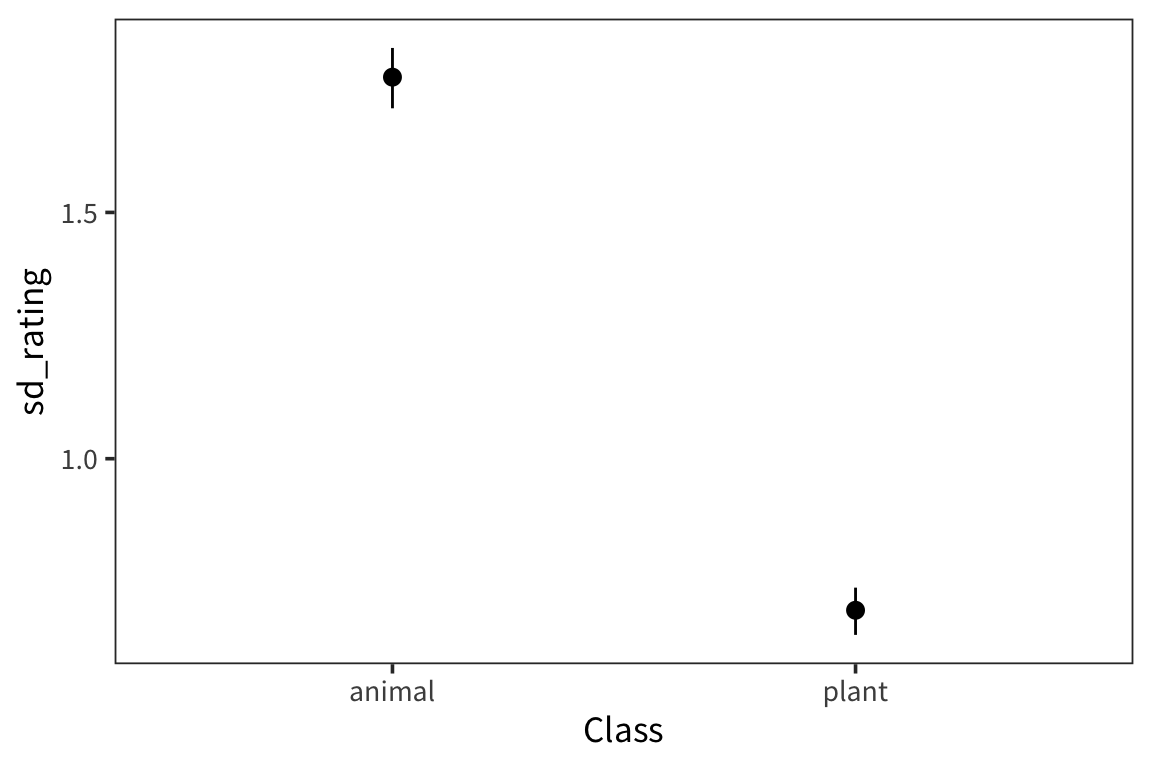

weight_summary <- weightRatings %>%

group_by(Class) %>%

sample_frac(size = 0.2, replace = FALSE) %>%

summarise(mean_rating = mean(Rating),

ci_lower_mean = ci_lower(resample_means(Rating, 1000)),

ci_upper_mean = ci_upper(resample_means(Rating, 1000)))

weight_summary## # A tibble: 2 x 4

## Class mean_rating ci_lower_mean ci_upper_mean

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 animal 3.32 3.07 3.59

## 2 plant 1.39 1.3 1.49ggplot(weight_summary, aes(x = Class)) +

geom_pointrange(aes(y = mean_rating, ymin = ci_lower_mean,

ymax = ci_upper_mean))

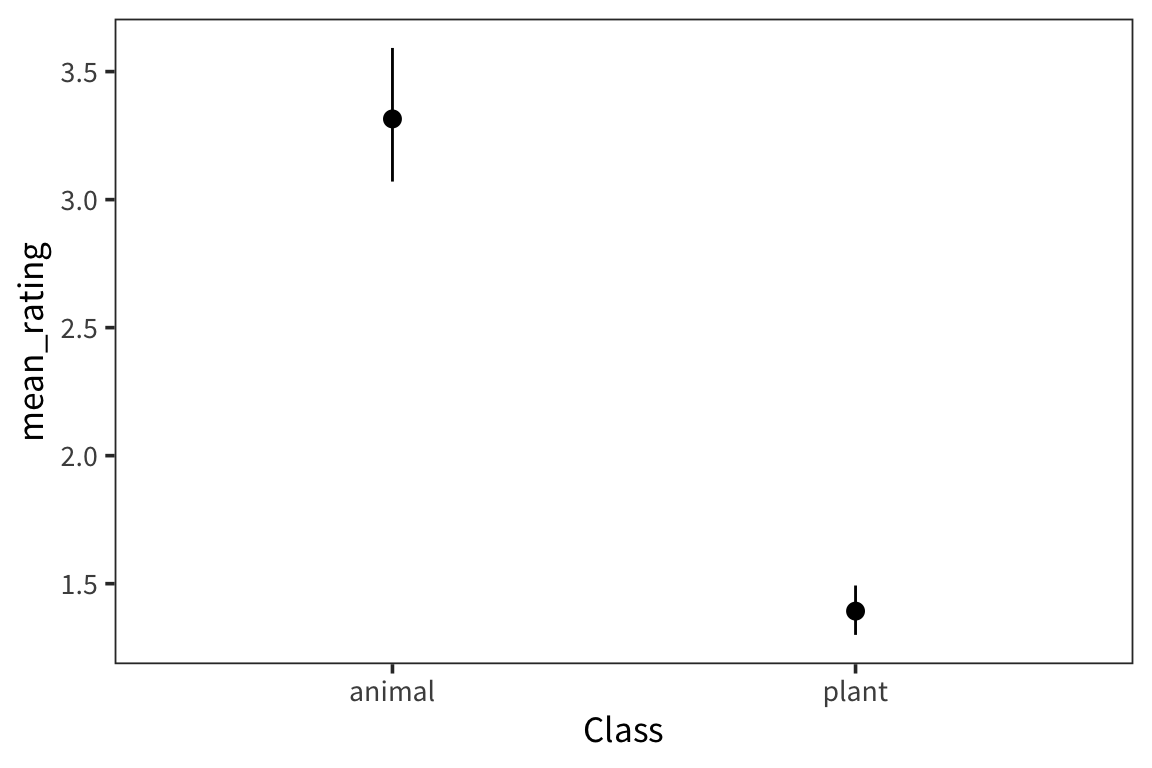

Parametric CIs:

std_error <- function(x) sd(x) / sqrt(length(x))

weight_summary <- weightRatings %>%

group_by(Class) %>%

summarise(mean_rating = mean(Rating),

se_rating = std_error(Rating),

ci_lower_mean = mean_rating - se_rating * 1.96,

ci_upper_mean = mean_rating + se_rating * 1.96)

weight_summary## # A tibble: 2 x 5

## Class mean_rating se_rating ci_lower_mean ci_upper_mean

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 animal 3.39 0.0585 3.27 3.50

## 2 plant 1.50 0.0262 1.45 1.55ggplot(weight_summary, aes(x = Class)) +

geom_pointrange(aes(y = mean_rating, ymin = ci_lower_mean,

ymax = ci_upper_mean))

Regular Expressions

So far we’ve interacted with strings just by looking at their lengths or some characters at specific indices. How would we do more complicated matching on kinds of strings? Regular expressions are a rich language for specifying patterns to match certain strings.

## [1] TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE## [1] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE## [1] TRUE## [1] FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE## [1] TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE## [1] TRUE TRUE FALSE## [1] TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE## [1] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE## [1] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE## [1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE## [1] TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE## [1] FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE## [1] "cat" "dat" "mycat"## [1] "cat" "dat" "mycat"## [1] "cat" "dat" NA "cat"## [1] "AT" "AT" "dog" "myAT"## [1] "c" "d" "dog" "myc"## [1] "ct" "dt" "dog" "myct"Useful resource: http://regexr.com/

Try it yourself…

For the rts.csv dataset:

Create a new dataset which only contains words that end with “s” or “r”.

Create another new dataset which only contains words that start with a consonant and contain the letter “o”.

Create a new column that has the words but with their first and last letters swapped

data_source <- "http://web.mit.edu/psycholinglab/www/data/" rts <- read_csv(file.path(data_source, "rts.csv")) rts_sr <- rts %>% filter(str_detect(Word, "[sr]$")) rts_consonants <- rts %>% filter(str_detect(Word, "^[^aeiou].*o")) rts_swapped <- rts %>% mutate(word_swapped = str_replace(Word, "^(.)(.*)(.)$", "\\3\\2\\1"))

Hypothesis testing

t-values and p-values

Now when we were working with the normal distribution, we converted data to the standard normal distribution so we could reason about probabilities. We called this z-scoring, and the resulting values are called z-values. We can think of the distances of sample means from the true mean \(\mu\) (in the case of known \(\sigma\)) as z-values. Now with the t-distribution, rather than z-values, we have t-values. A t-value is: \(\frac{\bar{x}-\mu}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}\), or: mean(X) - mu / (sd(X) / sqrt(length(X)))

For example we might be interested in if the true mean \(\mu\) is or is not equal to zero. Maybe we want to know if one group of participants is faster to respond than another on lexical decision. You can compute the differences in response times for a word, then we could look at the distribution of these differences in RTs and ask if the true mean of the differences is zero. If it is zero, then that would indicate the groups are equally fast.

Suppose we get a sample mean from our measurements. Then we can convert that into a t-value relative to zero (substituting zero for \(\mu\)). Suppose the t-value is 2 and we have 10 data points. Supposing the true value of \(\mu\) is 0, we can figure out what is the probability of my sample mean having a t-value of 2 or more:

## [1] 0.03827641We see that the probability of my getting a t-value of 2 was 0.038, if my true value of \(\mu\) is 0. That’s pretty unlikely. So I’d say the true value of \(\mu\) is probably something other than 0.

This is the logic of a p-value. Assume the true value of \(\mu\) is zero, or some other uninteresting value (the null hypothesis). Now get the probability of the t-value of my sample mean under that assumption. If it’s low, then I say that assumption was probably wrong.

Essentially, we convert our mean into a t-statistic, which is distributed according to a t-distribution with degrees of freedom. Then we get the probability of a t-distribution generating our t-value or greater, or -t-value or lesser.

This is called a t-test and you can do one much more straightforwardly in R.

##

## One Sample t-test

##

## data: d$value

## t = 37.67, df = 99, p-value < 2.2e-16

## alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 18.87418 20.97309

## sample estimates:

## mean of x

## 19.92363This gives you the t-value of the sample mean. It is 37.67; degrees of freedom is 99. So if the true mean is 0, then the probability that I would get this t-value for the mean of a sample is… really really really small.

In this case this is not particularly surprising since we were sampling the values of d from a normal distribution with \(\mu\) set to be 20.

The t.test() function also displays the confidence intervals calculated using the t-distribution. Here we are interested in whether this includes 0 or not. If the 95% confidence interval includes 0, then we cannot say with 95% confidence that the true \(\mu\) is not 0. If it does not include 0, then we can in fact say that.

##

## One Sample t-test

##

## data: d5$value

## t = 7.671, df = 4, p-value = 0.001553

## alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 13.00349 27.75596

## sample estimates:

## mean of x

## 20.37973## [1] 13.00349## [1] 27.75596This confirms our previously obtained CIs.

It’s actually very rare in psycholinguistics or psychology in general, that you would be interested in checking if some distribution is different from 0. More often you’ll want compare the means of two samples.

Let’s use the Baayen LexDec data again. Let’s say we want to test if people respond faster to nouns or verbs.

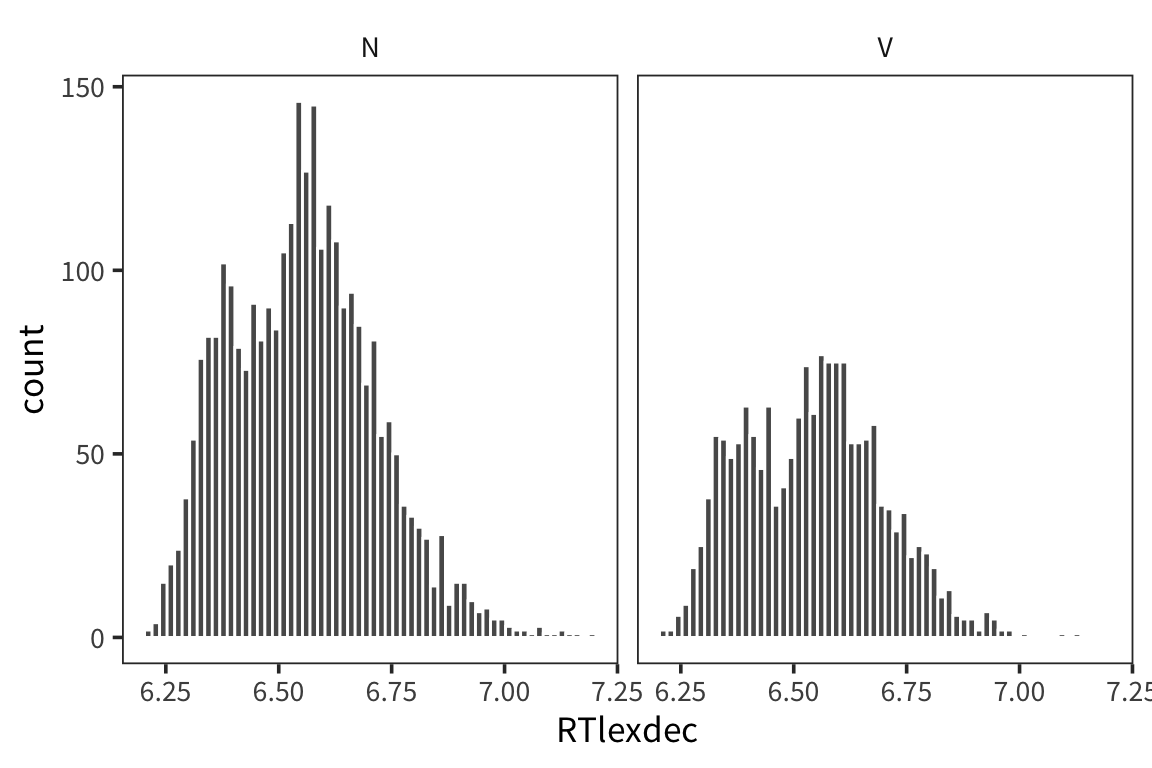

First plot the distributions of RTlexdec values, split up by whether they’re a noun or a verb…

ggplot(rts, aes(x = RTlexdec)) +

geom_histogram(bins = 60, color = "white") +

facet_wrap(~WordCategory)

As you can see it’s pretty unclear just from looking at these whether these are drawn from distinct distributions with distinct \(\mu\)s, or if they are just all samples from the same distribution.

Now let’s separate out our data and run a t-test.

verbs <- rts %>% filter(WordCategory == "V")

nouns <- rts %>% filter(WordCategory == "N")

verbs_rt <- verbs$RTlexdec

nouns_rt <- nouns$RTlexdec

t.test(verbs_rt, nouns_rt)##

## Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## data: verbs_rt and nouns_rt

## t = -2.6829, df = 3580.9, p-value = 0.007331

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.022141948 -0.003444228

## sample estimates:

## mean of x mean of y

## 6.541964 6.554758What you see is that relative to the one-sample t-test, your alternative hypothesis is now that the “true difference in means is not equal to 0” and you have a confidence interval for the difference of the means.

You might also notice that this is being called a Welch t-test which is different from a Student’s t-test. The Students t-test assumes that the 2 distributions have equal variances. You could run it that way:

##

## Two Sample t-test

##

## data: verbs_rt and nouns_rt

## t = -2.6534, df = 4566, p-value = 0.007997

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.02224543 -0.00334075

## sample estimates:

## mean of x mean of y

## 6.541964 6.554758And you get a very similar answer because these are large sample sizes. But it’s not clear that the variances are equal so the Welch version pools the variance across the two distributions.

There are tests to check if your variances are the same first but it actually makes much more sense to just default to the Welch test (which R does for you) because the Welch test does the right thing if your variances are different and it is basically identical to the Student’s t-test when the variances are the same. You can read more here: http://daniellakens.blogspot.com/2015/01/always-use-welchs-t-test-instead-of.html.

Using the combined standard errors, you can put a 95% confidence interval on the difference in true means here. We see that it does not include 0. So we can say with 95% confidence that there is some real difference between these groups, i.e. that these data were not generated from one call to rnorm with the same \(\mu\), but rather from someone calling rnorm twice, with two different \(\mu\) values. So we infer from this that there is some difference in the causal process that gave rise to our data.

The t-test also has alternative syntax. In the previous example, I split the data up into a vector of verb RTs and a vector of noun RTs and had them both entered as arguments. This extra step was kind of unnecessary because you could also write:

##

## Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## data: RTlexdec by WordCategory

## t = 2.6829, df = 3580.9, p-value = 0.007331

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.003444228 0.022141948

## sample estimates:

## mean in group N mean in group V

## 6.554758 6.541964This syntax will actually align better with other tests we will run.

Another version you might encounter is the paired t-test. This is what you would use if each individual datapoint in x corresponds to a datapoint in y. For example if you have data from a pre-test and a post-test with some intervention in between and you want to see if that intervention had an effect on the means. Then you use t.test(x, y, paired = TRUE).

Null hypothesis testing and p-values

This is the basic logic of how we do frequentist statistics. We choose some uninteresting NULL HYPOTHESIS, like the difference is 0.

Then we show that, under this uninteresting hypothesis, the data that we have are very unlikely. If the probability of our data under the null hypothesis is below some threshold, we say that we have a SIGNIFICANT EFFECT. The idea is that the observed difference leads us to conclude, from the sheer unlikeliness of our data under the null hypothesis, that the null hypothesis is false, and something else must be true.

IMPORTANT: Finding a p-value < 0.05 does NOT mean that there is a 95% chance there really is a difference.

You should think critically about whether this is a good way to draw inferences. In particular, does it make sense to have a constant threshold for significance. Typically we want p is less than .05. This is equivalent to saying some 95% confidence interval does not include 0.

Try it yourself…

Compare the naming response times (RTnaming) of old and young participants in the

rtsdataset.Write down in English what, test you used, what the stats are, and what you can conclude on the basis of this test.

## ## Welch Two Sample t-test ## ## data: RTnaming by AgeSubject ## t = 226.19, df = 4335.5, p-value < 2.2e-16 ## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## 0.3390249 0.3449533 ## sample estimates: ## mean in group old mean in group young ## 6.493500 6.151511A Welch Two Sample t-test reveals that younger participants were significantly faster to respond than older participants (t(4335.5) = 226.19, p < 0.001).

Power

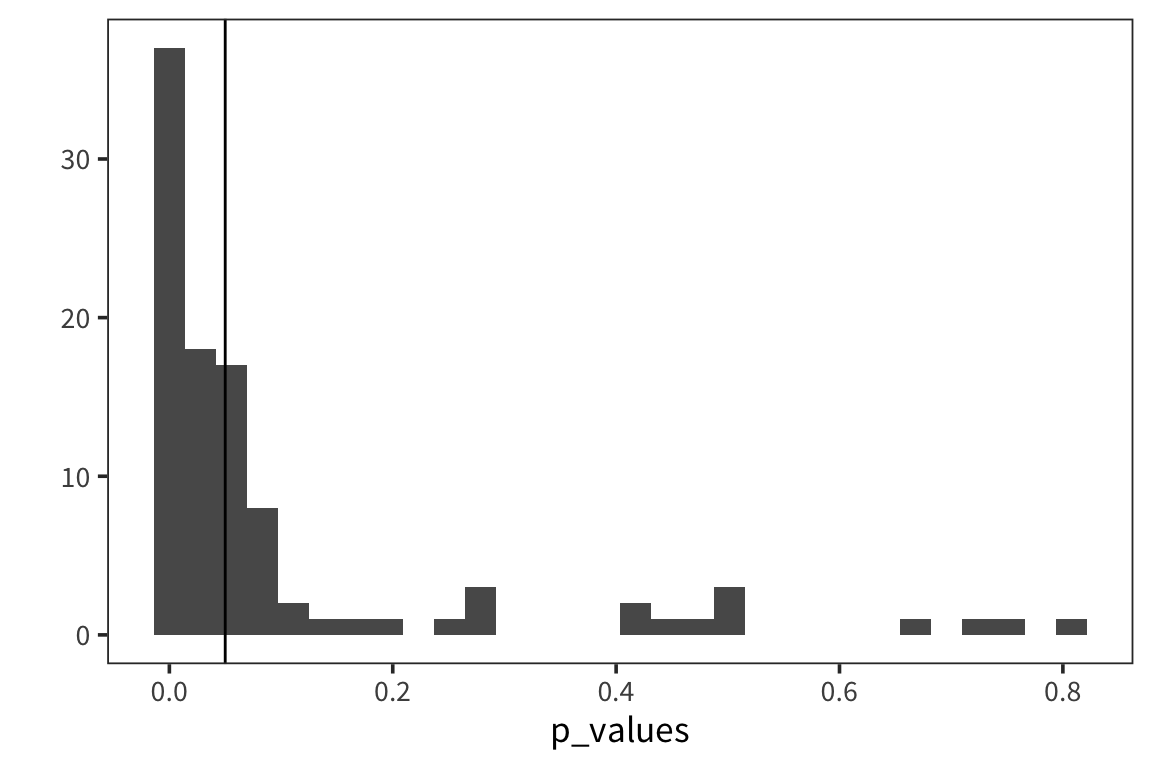

Let’s think about the long-run distributions of p-values. Let’s say we have samples from 2 different distributions, we test if they are different, and we replicate 1000 times.

experiment <- function() {

sample1 <- rnorm(1000, 20, 10)

sample2 <- rnorm(1000, 21, 10)

p_value <- t.test(sample1, sample2)$p.value

return(p_value)

}

p_values <- replicate(100, experiment())

qplot(p_values, geom = "histogram") + geom_vline(xintercept = 0.05)

So here we have a real effect but maybe it’s on the small side, so the majority of p-values falls between 0 and 0.05 but there’s a few that are above 0.05 and in fact, some are quite large. This is showing that if you have a small difference, if you replicate your experiment or other labs replicate your experiment, some proportion of the time, you will get a p-value > 0.05 just by chance. These are Type II errors: cases where you are not rejecting the null but actually there is a difference.

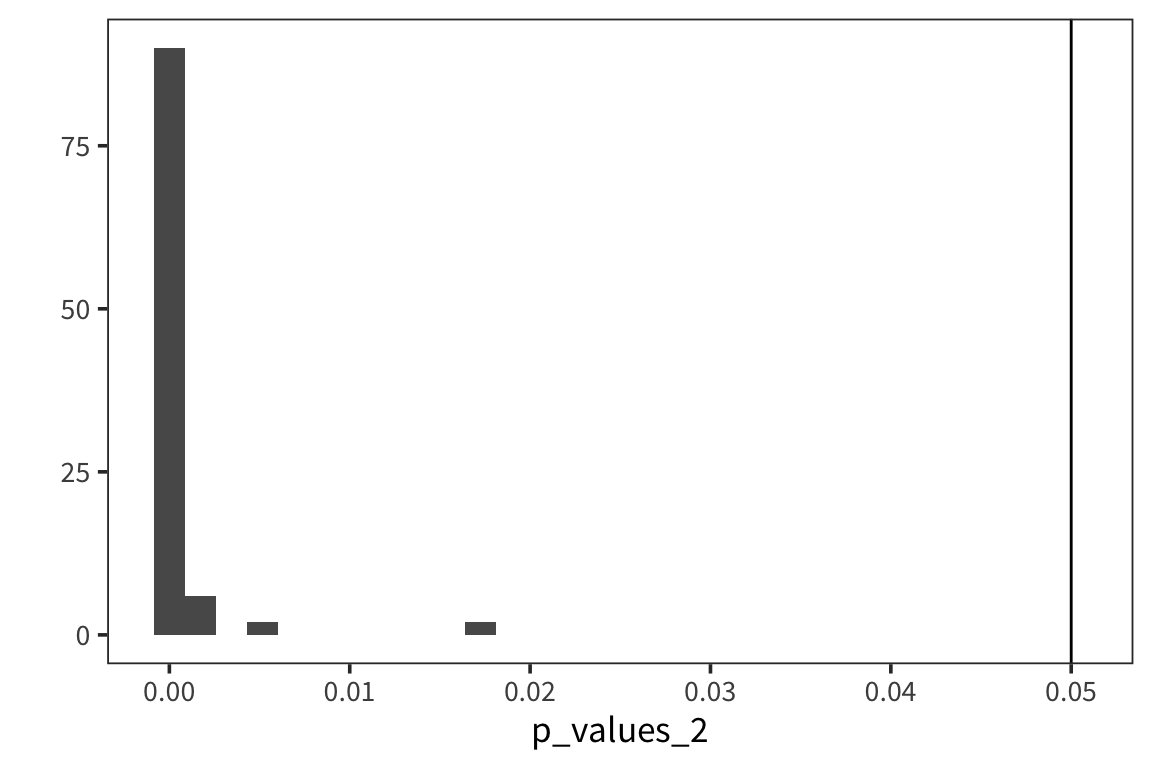

But if your effect is bigger…

experiment_2 <- function() {

sample1 <- rnorm(1000, 20, 10)

sample2 <- rnorm(1000, 22, 10)

p_value <- t.test(sample1, sample2)$p.value

return(p_value)

}

p_values_2 <- replicate(100, experiment_2())

qplot(p_values_2, geom = "histogram") + geom_vline(xintercept = 0.05)

You can see that there are way more effects between 0 and 0.05. In fact many of these are less than 0.01.

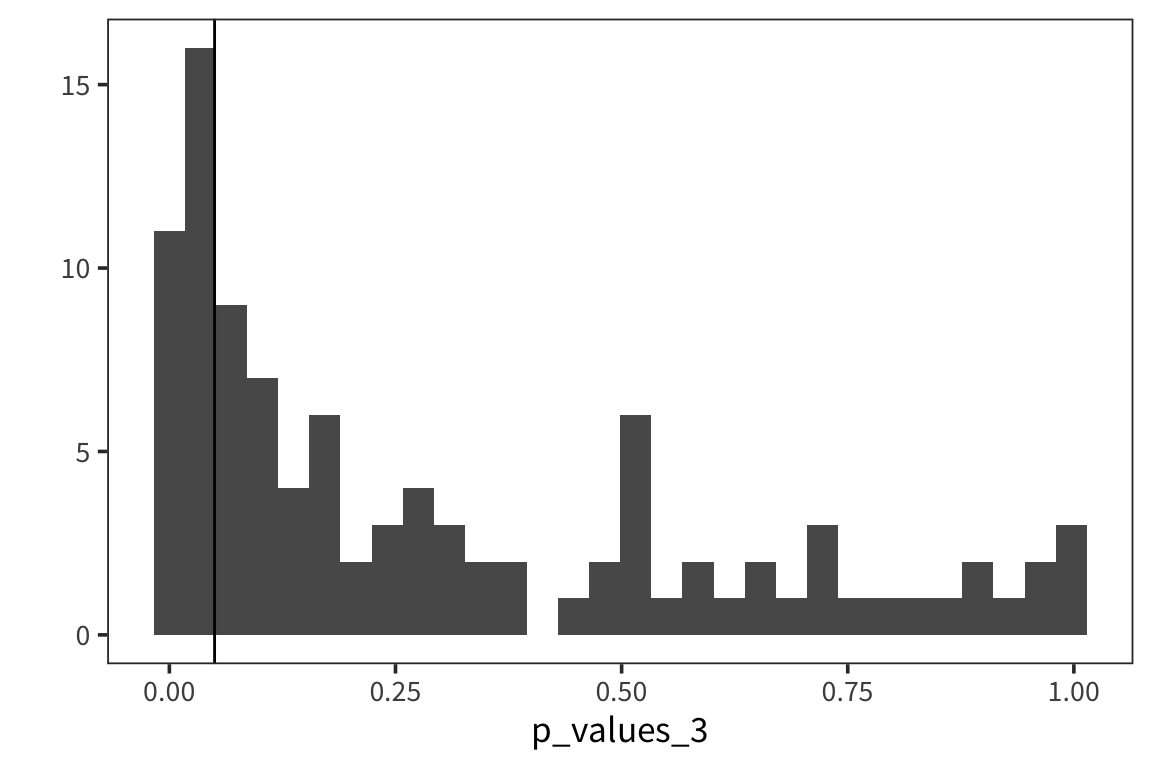

Now let’s try a tiny effect…

experiment_3 <- function() {

sample1 <- rnorm(1000, 20, 10)

sample2 <- rnorm(1000, 20.5, 10)

p_value <- t.test(sample1, sample2)$p.value

return(p_value)

}

p_values_3 <- replicate(100, experiment_3())

qplot(p_values_3, geom = "histogram") + geom_vline(xintercept = 0.05)

The smaller the effect, the larger the proportion of p-values above 0.05.

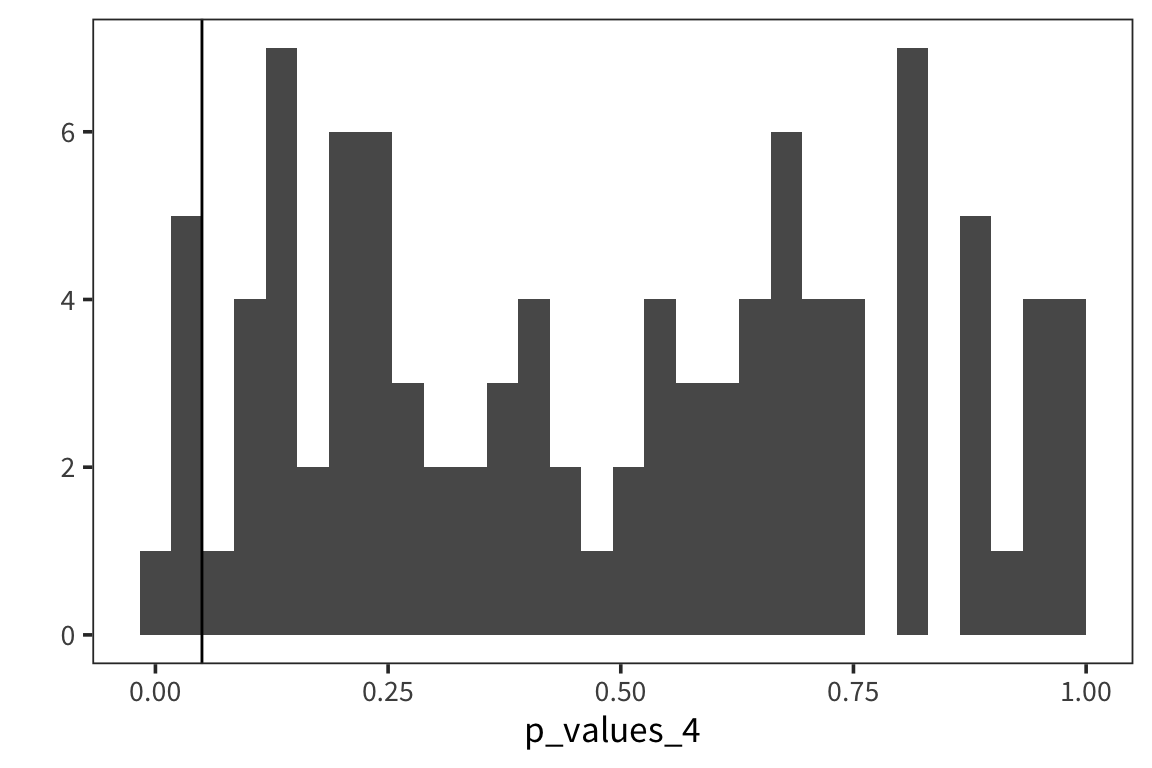

And of course when there is no effect…

experiment_4 <- function() {

sample1 <- rnorm(1000, 20, 10)

sample2 <- rnorm(1000, 20, 10)

p_value <- t.test(sample1, sample2)$p.value

return(p_value)

}

p_values_4 <- replicate(100, experiment_4())

qplot(p_values_4, geom = "histogram") + geom_vline(xintercept = 0.05)

The p-values are uniformly distributed.

Note that some proportion of p-values, specifically 5%, is below 0.05 – these are Type I errors: cases where you are rejecting the null despite the fact that there is no effect.

Returning to Type II errors: when you fail to reject the null when the null hypothesis is false (\(\beta\)).

1-\(\beta\) is what is called power. Said another way, power is the probability that if an effect exists, you will find it – clearly you want power to be as high as possible for any test you run.

Effect size and sample size

Very briefly, measures of effect size, such as Cohen’s \(d\) can give you a standardized measure of how big a difference is that you can compare across studies, measures, sample sizes, etc. If you have some information about the size of the effect you’re after, either from your own prior work, or the literature, you can use that to plan an appropriately powered study:

##

## Two-sample t test power calculation

##

## n = 393.4067

## delta = 1

## sd = 5

## sig.level = 0.05

## power = 0.8

## alternative = two.sided

##

## NOTE: n is number in *each* groupThis is saying that you would need ~393 people per condition to detect a difference in means of 1 with 80% power.

##

## Two-sample t test power calculation

##

## n = 99.08057

## delta = 2

## sd = 5

## sig.level = 0.05

## power = 0.8

## alternative = two.sided

##

## NOTE: n is number in *each* groupWith a bigger effect size, we need fewer subjects for the same level of power.

##

## Two-sample t test power calculation

##

## n = 50

## delta = 2

## sd = 5

## sig.level = 0.05

## power = 0.5081451

## alternative = two.sided

##

## NOTE: n is number in *each* groupIf we instead put in a number of subjects, we get a power level.